In 2012, Benny Briga opened a café in a four-by-six-meter kiosk on the corner of Levinsky and Merhavia Streets in Tel Aviv. The space was smaller than most people’s bedrooms. The neighborhood spice merchants told him, with a mixture of affection and pity, that nobody would buy coffee from him, everyone had their own pots at home.

They were spectacularly wrong.

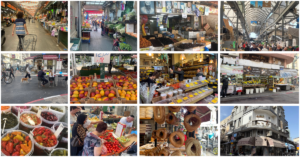

Café Levinsky 41 became the epicenter of the Tel Aviv food scene, reviving a nearly-forgotten Israeli beverage tradition and transforming Levinsky Market from a neglected immigrant enclave into one of the city’s most celebrated food destinations.

From Restaurant Kitchens to a Corner Kiosk in Levinsky Market

Benny Briga was born in Or Yehuda in 1975, in what he describes as a house with a lot of pots always cooking. After military service and two years traveling through South America, he found his calling at Manta Ray restaurant, working his way up to sous-chef and later became head chef at a fish restaurant in Herzliya before opening his own place in Neve Tzedek called Casserole, serving Iraqi and Tripolitan dishes alongside nearly 200 different kinds of arak.

When Casserole closed, Briga has spoken about how personally difficult the experience was, how tightly a restaurant can become bound up with a chef’s identity, and how hard it is to let go.

But in 2012, he was ready for something completely different. He’d moved to Nahalat Binyamin and spent time wandering through Levinsky Market. He knew the time had come for it to be rejuvenated and wake up.

He partnered with Moshe Prizmant, a former Casserole regular and businessman, and they found their spot, a small kiosk run by what Briga describes as a hefty guy who was drunk by 10 in the morning and always looking to pick fights. When it closed, they signed the contract within an hour.

Building Something from Nothing

Briga and Prizmant renovated the tiny space themselves, installing a vintage 1964 La Favorita espresso machine that would become the café’s beating heart. When the city gave them trouble about placing chairs on the sidewalk, they bought a 1975 Susita pickup truck and let people sit on seats in the open truck bed.

That old Susita, once spruced up with plants and flowers, became more than transportation. It emerged as the café’s symbol, a testament to creative improvisation and the rebellious spirit that would define the market’s transformation. After Levinsky Street was converted into a pedestrian walkway, the truck could no longer remain on the street, but a small model of the Susita now sits on display, preserving its role in the café’s story.

Reviving Gazoz, Israel’s Forgotten Soda

Gazoz is a traditional Israeli soda once common in Tel Aviv kiosks, made from carbonated water sweetened with flavored syrups, and first sold from a kiosk on Rothschild Boulevard.

For many Israelis, gazoz lives more in memory than in daily life. It’s a drink most people under forty never encountered firsthand, but one their grandparents remember clearly, carbonated water sweetened with colorful syrups, sold from kiosks across Tel Aviv. As Haaretz reported in 1930, the soda trade had flourished in Israel and really gained a name in Tel Aviv. The first soda factories opened in Jaffa in the 19th century, and by the early 20th century, dozens of kiosks around Tel Aviv sold these refreshing drinks, social hubs where workers, merchants, and neighbors gathered in the sweltering Mediterranean heat.

Then supermarkets came. Modern soft drinks flooded the market. By the 1990s, gazoz had become a nostalgic memory, not something you could actually buy. As Briga later reflected in his writing, gazoz was never intended as a novelty or indulgence, but as an everyday, nonalcoholic drink meant to refresh across ages and hours of the day.

Briga brought it back. But he didn’t just recreate the old artificially-flavored syrup drinks. He transformed gazoz into something entirely new, all-natural ingredients, seasonal produce, botanical complexity that rivaled professional cocktail bars.

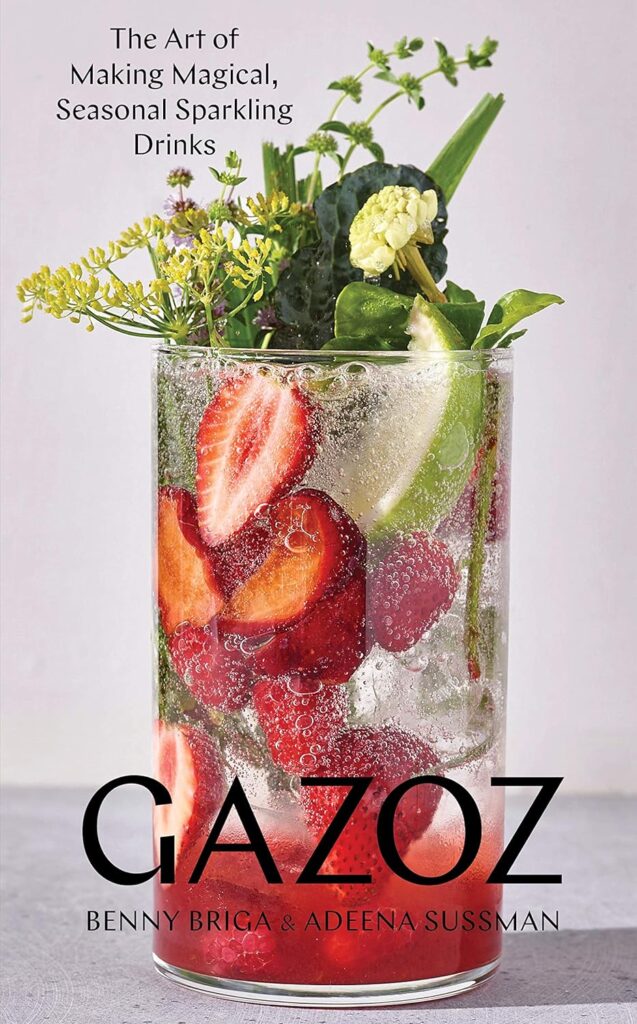

A decade after he began improvising gazoz at Café Levinsky 41, Briga teamed up with cookbook author Adeena Sussman to translate his free‑form, market‑driven approach into a home kitchen language. Together they wrote Gazoz, a book that captures his methods for sweet fermentation and his philosophy of turning seasonal fruit, herbs, and syrups into endlessly adaptable sparkling drinks.

The Art of the Improvised Gazoz at Café Levinsky 41

Briga explains that from the start, he knew he wanted to work with sweets, liqueurs, and jams because the whole market was already saturated with pickles. What ultimately brought it all together was his childhood among orchards, his interest in organic and sustainable agriculture, and his approach to what he describes as sweet fermentation.

As Briga later wrote in his book Gazoz, this approach centers on suspending fruit in sugar and allowing time, natural yeasts, and low-oxygen conditions to do their work. Through this process, the fruit concentrates, deepens, and transforms, developing layered flavors through a slow, patient cycle of fermentation and preservation.

There are no set recipes at Café Levinsky 41. Each drink is improvised based on the season, the customer’s wishes, and Briga’s own inclinations. No two drinks are ever the same. As Briga later wrote in his book Gazoz, this flexibility is central to the drink itself, built around choice, allowing the fruit, sweetness, and flavor combinations to shift in response to the moment rather than fixed formulas.

He might grind juniper berries and allspice in a large clear glass, add green grape leaves, lemongrass and basil with purple flowers, then melon soaked in prune juice and crimson fig halves, filling it with soda water. The result looks like something from an explorer’s botanical notebook, each glass a work of edible art.

The building blocks include rows of jugs filled with natural syrups made from seasonal fruits, figs, watermelon, apples, Nashi pears, limes, guava, apricots, along with spices like juniper, star anise, vanilla and Persian lemon. Some fruits are preserved briefly with sugar, honey, or stevia, others ferment for months or even years, developing complex flavors through patient aging.

The ingredients come from everywhere, urban gardens and trees around Tel Aviv, Briga’s own plantings in Florentin’s community garden, fresh herbs twice a week from a nursery in Kfar Vitkin, and donations from friends and customers who bring him fruit. In his writing, Briga has described this approach as emerging from the meeting point of city life and nature, where the urban environment itself becomes part of the ingredient landscape.

And while the kiosk’s license doesn’t permit alcohol sales, Briga discovered that adding locally made gin to his gazoz creates flavors that rival professional cocktail bars. The botanical complexity of natural syrups combined with quality gin transforms simple refreshment into sophisticated beverage art.

Instagram Famous, But for Good Reason

By the mid-2010s, Café Levinsky 41 had become a required stop on Tel Aviv food tours and a frequent reference point in international food media coverage of the city’s evolving culinary scene.

The artisanal gazoz, served with abundant fresh herbs erupting from the glass became wildly Instagram-famous around 2013 to 2014. The drinks were photogenic, delicious and unlike anything available anywhere else in Israel.

But the phenomenon went deeper than social media virality. Café Levinsky 41 represented something profoundly meaningful, the revival of authentic Israeli food culture through innovation rather than nostalgia.

Briga wasn’t trying to recreate his grandmother’s gazoz. He was creating something new that honored tradition while embracing contemporary values, organic agriculture, seasonal eating, urban foraging, artisanal production. The café embodied what Levinsky Market itself was becoming, a place where immigrant culinary traditions could evolve without losing their soul.

A Philosophy of Radical Seasonality

While gazoz became the signature offering, the café developed into a complete neighborhood gathering place.

The café operates with radical seasonality and improvisation. What’s available today might not exist tomorrow. It’s the opposite of chain café standardization, a defiant insistence on craft, locality, and the creative process.

How Café Levinsky 41 Transformed Levinsky Market

Café Levinsky 41’s success became inseparable from Levinsky Market’s broader transformation during the 2010s. When Briga and Prizmant opened in 2012, the market was still somewhat rundown, veteran spice shops and delicatessens serving a working-class clientele, surrounded by light industrial workshops and former immigrant boarding houses.

By 2015, the market had become one of Tel Aviv’s hottest culinary destinations. Food tours brought groups through daily. International food magazines featured it in must-visit lists. Condé Nast Traveler called it one of the globes best markets. Young Tel Avivians moved to Florentin seeking both the authenticity that had been sanitized out of northern neighborhoods and less expensive rent.

The tiny kiosk and its botanical sodas became the market’s symbol, proof that innovation could coexist with tradition, and that a four-by-six-meter space could change a neighborhood’s destiny.

And unlike typical gentrification that displaces original businesses, Levinsky Market’s transformation preserved its veterans. Pereg Gourmet, Habshush Spices, Yom Tov Delicatessen, Bourekas Penso, all remained, now operating alongside new establishments. Traditional vendors benefited from increased foot traffic. New businesses drew inspiration from the market’s authentic character. A virtuous cycle emerged where old and new reinforced rather than threatened each other.

The Street That Woke Up

By 2020, after years of merchant advocacy, the market section of Levinsky Street officially became a pedestrian mall, closed to vehicular traffic. The street that once choked with traffic now fills with strolling shoppers, people sitting at café tables, tour groups tasting their way through vendors, children running between spice shops.

The gazoz kiosk sits at the heart of this transformed landscape.

A Tiny Space with Lasting Impact

At its core, the story of Café Levinsky 41 is also the story of Levinsky Market and Tel Aviv’s evolving food culture, where tradition, innovation, and place intersect in a way that reshaped the city’s culinary identity.

More than a decade after opening, Café Levinsky 41 remains a cornerstone of Levinsky Market. The vintage Susita no longer sits outside, but a small model of the truck now recalls its role in the café’s early years. The 1964 La Favorita has given way to a modern espresso machine, yet Benny Briga still improvises seasonal botanical sodas.

The café stands as proof that small-scale, craft-focused, tradition-honoring businesses can not just survive but thrive in contemporary urban environments. It demonstrates that gentrification doesn’t have to mean displacement, that new audiences can appreciate old traditions, that innovation and authenticity are not opposites but partners.

Every glass of gazoz served, herbs erupting from the rim, natural syrups creating layers of color, carbonation lifting botanical aromatics into the air, represents a small victory for craft, locality, and the stubborn insistence that commerce can create beauty.

Those skeptical spice merchants were wrong. People did buy coffee. They bought gazoz. They gathered around a tiny kiosk and made it the heart of a neighborhood’s revival.

Levinsky Market woke up. And a four-by-six-meter kiosk with a vintage truck and a chef who knew how to honor tradition while embracing innovation was the alarm clock.

Cafe Levinsky

Taste Levinsky Market for yourself

Want to explore the flavors, stories, and hidden corners of Levinsky Market with a local guide? Book a private Levinsky Market food tour and eat your way through Tel Aviv’s most iconic food street.